The Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances were all about Highlanders of the 18th century being pushed off their land and moved to the coast - making way for sheep !

Highland Clearances were the forced displacement of highlanders during the 18th and 19th centuries. They led to mass emigration to the sea coast, the Scottish Lowlands and the North American colonies. The clearances were part of a process of agricultural change but were particularly notorious due to the late timing, the lack of legal protection for year-by-year tenants under Scottish law, the abruptness of the change from the traditional clan system and the brutality of many evictions.

In 1725 General Wade raised the independent companies of the Black Watch as a militia force to keep peace in the unruly Highlands. This increased exodus of Highlanders to the Americas. Increasing demand in Britain for cattle and sheep and the creation of new breeds of sheep such as the black-faced, which could be reared in the mountainous country, allowed higher rents for landowners and chiefs to meet the costs of their aristocratic lifestyle. As a result, families living on a subsistence level were displaced, exacerbating the unsettled social climate. In1792 tenant farmers from Strathrusdale led a protest against the policy by driving over 6,000 sheep off the land surrounding Ardross. This action was dealt with at the highest levels in government, with the Home Secretary Henry Dundas getting involved. The Black Watch was mobilised; it halted the drive and brought the ringleaders to trial. They were found guilty, but later escaped custody and disappeared.

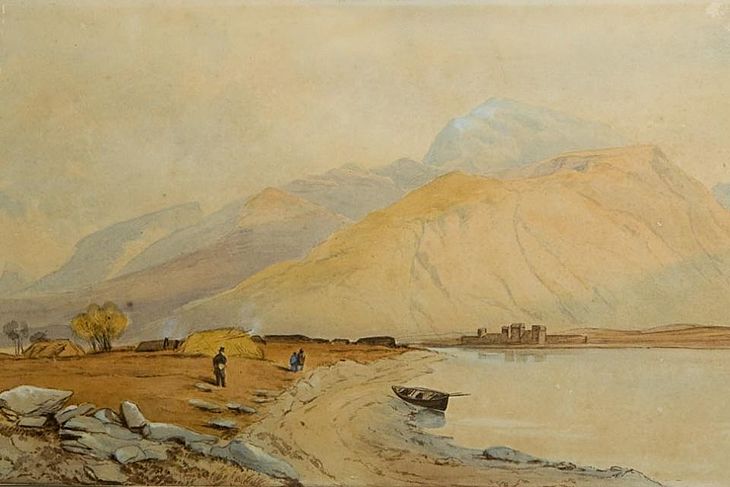

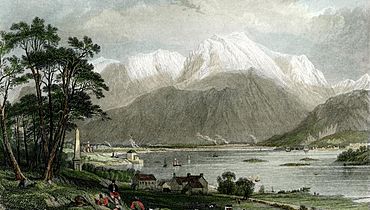

1792 became known as the "Year of the Sheep" to Scottish Highlanders. The people were accommodated in poor crofts or small farms in coastal areas where farming could not sustain the communities and they were expected to take up fishing. In some villages the conditions were so harsh that, while the women worked, they had to tether their livestock and even their children to rocks or posts to prevent them being blown over the cliffs.

Others were put directly onto emigration ships to Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, Ontario and the Carolinas. Elizabeth Gordon, the 19th Countess of Sutherland, and her factor, Patrick Sellar, were especially cruel and their names are reviled in the county of Sutherland to this day. Donald McLeod, a Sutherland crofter, later wrote about the events he witnessed: "The consternation and confusion were extreme. Little or no time was given for the removal of persons or property; the people striving to remove the sick and the helpless before the fire should reach them; next, struggling to save the most valuable of their effects. The cries of the women and children, the roaring of the affrighted cattle, hunted at the same time by the yelling dogs of the shepherds amid the smoke and fire, altogether presented a scene that completely baffles description — it required to be seen to be believed. A dense cloud of smoke enveloped the whole country by day, and even extended far out to sea. At night an awfully grand but terrific scene presented itself — all the houses in an extensive district in flames at once. I myself ascended a height about eleven o'clock in the evening, and counted two hundred and fifty blazing houses, many of the owners of which I personally knew, but whose present condition — whether in or out of the flames — I could not tell. The conflagration lasted six days, till the whole of the dwellings were reduced to ashes or smoking ruins. During one of these days a boat actually lost her way in the dense smoke as she approached the shore, but at night was enabled to reach a landing-place by the lurid light of the flames."

In 1725 General Wade raised the independent companies of the Black Watch as a militia force to keep peace in the unruly Highlands. This increased exodus of Highlanders to the Americas. Increasing demand in Britain for cattle and sheep and the creation of new breeds of sheep such as the black-faced, which could be reared in the mountainous country, allowed higher rents for landowners and chiefs to meet the costs of their aristocratic lifestyle. As a result, families living on a subsistence level were displaced, exacerbating the unsettled social climate. In1792 tenant farmers from Strathrusdale led a protest against the policy by driving over 6,000 sheep off the land surrounding Ardross. This action was dealt with at the highest levels in government, with the Home Secretary Henry Dundas getting involved. The Black Watch was mobilised; it halted the drive and brought the ringleaders to trial. They were found guilty, but later escaped custody and disappeared.

1792 became known as the "Year of the Sheep" to Scottish Highlanders. The people were accommodated in poor crofts or small farms in coastal areas where farming could not sustain the communities and they were expected to take up fishing. In some villages the conditions were so harsh that, while the women worked, they had to tether their livestock and even their children to rocks or posts to prevent them being blown over the cliffs.

Others were put directly onto emigration ships to Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, Ontario and the Carolinas. Elizabeth Gordon, the 19th Countess of Sutherland, and her factor, Patrick Sellar, were especially cruel and their names are reviled in the county of Sutherland to this day. Donald McLeod, a Sutherland crofter, later wrote about the events he witnessed: "The consternation and confusion were extreme. Little or no time was given for the removal of persons or property; the people striving to remove the sick and the helpless before the fire should reach them; next, struggling to save the most valuable of their effects. The cries of the women and children, the roaring of the affrighted cattle, hunted at the same time by the yelling dogs of the shepherds amid the smoke and fire, altogether presented a scene that completely baffles description — it required to be seen to be believed. A dense cloud of smoke enveloped the whole country by day, and even extended far out to sea. At night an awfully grand but terrific scene presented itself — all the houses in an extensive district in flames at once. I myself ascended a height about eleven o'clock in the evening, and counted two hundred and fifty blazing houses, many of the owners of which I personally knew, but whose present condition — whether in or out of the flames — I could not tell. The conflagration lasted six days, till the whole of the dwellings were reduced to ashes or smoking ruins. During one of these days a boat actually lost her way in the dense smoke as she approached the shore, but at night was enabled to reach a landing-place by the lurid light of the flames."